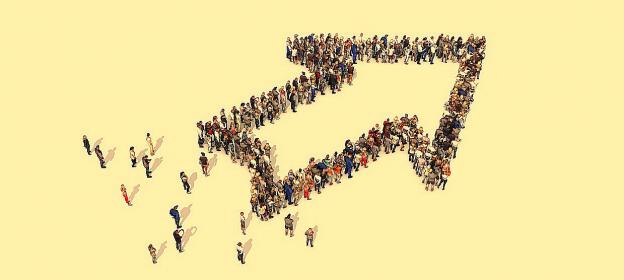

Even firms that typically prefer to centralize decisions needn’t miss out on the benefits of opening up their strategy making.

Strategy making has traditionally been the purview of the top management team. Leaders in the inner circle of organisations pride themselves in being the architects of their plans. Open strategy is a more recent concept that consists of involving a wider community in the exercise. Benefits are well known. For instance, ideas can be drawn from a larger, diverse pool, and giving staff a voice can boost their commitment. Despite these advantages, open strategy remains an acquired taste for many top-down strategic planners.

However, unless a company has an absolute dream team at the helm and a stellar track record to show for it, it can be hard to oppose the trend towards openness. The question becomes how to manage the community-focused process, especially in centralised organisations, where control tends to be concentrated in the hands of the few.

In our paper, “Opening Up: How Centralization Affects Participation and Inclusion in Strategy Making”, we show that open strategy can be carried out in both centralised and decentralised firms, albeit following different recipes. To better understand the differences, we suggest drawing a distinction between the practices of participation and inclusion that underpin the process.

Open strategy via participation and inclusion

A wide range of people can have a stake in a firm’s strategy. These include the staff, of course, but also customers, activists and even trade journalists, among others. There are two main ways to engage them when setting corporate strategy in an open fashion. The first one is called participation and the second, inclusion.

Participation is about increasing stakeholders’ input to inform strategy decisions. Relevant activities include surveys, interviews and any other information gathering. They consist of one-off transfers of knowledge – similar to the passing of a ball.

Inclusion is about creating and sustaining a community of stakeholders tasked to look into an ongoing stream of strategy issues. Prime examples are work groups and task forces. These communities come together to share ideas and decision making over a period of time.

Two company vignettes

Our paper describes how two public companies – one centralised, the other less so – engaged in open strategy to define their responses to the e-commerce revolution of the mid-1990s. These vignettes illustrate how a firm’s degree of centralisation affects participation and inclusion in strategy making.

Taking into consideration the two phases of strategy making – alternatives generation and idea selection – the differences can be schematised as below:

image: https://knowledge.insead.edu/sites/www.insead.edu/files/images/capture-open_strategy.jpg

Open strategy in a decentralised company

Open strategy in a decentralised company

At HealthCo, a large decentralised healthcare company, inclusion was practised on a broad scale in the first phase, as 80 employees and other stakeholders were asked to collaboratively think up ideas for the firm’s internet business. Participation (e.g. basic input-gathering) was present, but limited to a focus group involving customers and strategic partners.

The team tasked with selecting the final idea was a subset of the larger group in charge of generating alternatives. At the end of the first phase, a director who had been involved in it requested to work full-time on the idea-selection team so he could continue pushing for his idea. Other participants, also keen to champion their own ideas, followed suit. Strategy evolved in the hands of a strong collaborative community who stayed connected over time.

A centralised firm example

The case of FoodCo, a famous food manufacturing company, illustrates how a centralised company implemented the concept of open strategy. In the first phase, FoodCo generated the bulk of alternatives through a large number of internal and external surveys, meetings and other information-gathering routines that already existed within the organisation. This showed a heavy reliance on participation.

FoodCo did use some inclusion, but on a smaller scale. It created an e-commerce team of 20 employees and tasked them with deliberating the best internet strategy based on the gathered information. Separate category business teams were given a similar mandate.

During the idea selection phase, FoodCo again relied on inclusion, but further reduced its scale as the final strategy discussions were between the e-commerce team and the firm’s senior executives.

Transparency

One notable difference between the two companies was seen in the flow of ideas from one strategy-making phase to the next. In the centralised firm, there was no ‘idea championing’ and carryover between the two phases, as these were performed by largely separate groups of people. Thus there was a decoupling of ideas from participants. In the second phase, alternatives were filtered based on what the final team thought was relevant. Most people who generated alternatives had little to no visibility on the selection phase.

Unsurprisingly, the reduced scale of inclusion as well as the lack of idea championing and carryover decreased the transparency of the exercise in the centralised firm example.

Implications

Open strategy is not an all-or-nothing matter. Rather, it can be thought of as a continuum of options.

At one end of the continuum, more people partake in the strategy-making process, over a longer period of time, increasing the proportion of people likely to be committed to the final idea. One potential drawback of inclusive practices (especially their scaled-up versions) could be their costs in terms of time and coordination. Care should also be taken to ensure the diversity of those included in the process.

In addition, depending on the DNA of the firm, high inclusion and transparency may lead to tension if senior management sees its authority being challenged. Such tension can be dealt with by leaning towards the other end of the continuum, with more emphasis on participation (which still taps the wisdom of the crowd). In such a case, the worry is that staff lower in the hierarchy may think their involvement is mostly symbolic and thus feel disengaged. Open strategy is a balancing act.

The distinction between participation and inclusion may be useful in managing stakeholders’ expectations with regard to their involvement. If firms are better able to communicate how employees fit in the strategy planning process, some misperceptions and misgivings may be avoided.

In a completely closed process, there is inherent conflict between executives with an exclusive management style and the employees asked to carry out strategies which they had no hand in creating. By opening the process, even a little, firms can benefit from the wisdom of the crowd via the practices of participation and inclusion. As each practice yields a different level of commitment, a firm may need to ask itself if it only needs input, or if it also wants to win hearts.

Daniel Mack recently defended his doctoral dissertation at INSEAD and will be joining Singapore Management University as an Assistant Professor of Strategic Management in July 2017.

Gabriel Szulanski is a Professor of Strategy and the Chair of the Strategy Area at INSEAD.

Read more at https://knowledge.insead.edu/strategy/strategy-making-how-to-tap-the-wisdom-of-the-crowd-6621#Igfoc8aTORuOYcxD.99